|

Ephraim Miner |

Ephraim Miner was a common, God-fearing farm boy from a rural Southwestern Pennsylvania county whose life was profoundly changed as a fighter but primarily as a sidelined observer in the Civil War. He suffered physical anguish at the Battle of Fredericksburg but no doubt endured significant emotional guilt as, enduring deafness, sore back and frostbitten feet, he sat out the rest of the war while many in his former regiment mates were wounded and killed in some of the most important battles of the war – Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, The Wilderness, Petersburg and finally the end at Appomattox.

Set into the broader sweeping context of Civil War history, Ephraim bore the first of his injuries during a tragic, one-sided slaughter at Fredericksburg, pitting the Army of the Potomac under the command of Ambrose Burnside against the Army of Northern Virginia led by Robert E. Lee. Among the other generals directly involved were George Meade (Union), James Longstreet, Stonewall Jackson, Jubal Early, A.P. Hill, John Bell Hood and Jeb Stuart (Confederate), names deeply imbued in American military legend. Three times as many Union soldiers were killed at Fredericksburg than Confederates, but Ephraim – fortunately – survived. It is entirely possible that any of these generals actually could have laid eyes upon Ephraim for an instant, as he was among the massing blue tide of Union soldiers crossing the Rappahannock River and assaulting Fredericksburg in the cold, foggy pre-Christmas days of Dec. 11-15, 1862.

In later years, Ephraim told his children and grandchildren of the “rivers of blood” that ran at Gettysburg, which, while true, he did not see, because in fact he was not at that battle. Rather, he was in a military hospital in West Philadelphia. He shared tales of having been so hungry that if he had seen a piece of meat lying in the mud, he gladly would have eaten it.

He told his grandchildren about when for a number of frightening nights in a row, one of the guards of his camp would be shot in the darkness. Each time, a large pig could be seen grazing some distance away. Finally, one frightened guard decided to shoot any living thing that came near. Sure enough, Ephraim recounted, the pig came around the next night, and promptly was shot dead. Upon examination, a Confederate’s body was discovered under the camouflage of the pigskin. Tied to the pig’s tail was the gun he dragged and used to pick off the Union guards.

As an old man, Ephraim relished attending Civil War reunions, perhaps making up for the time he spent convalescing during the actual conflict. At death, he left instructions that he be buried in his old uniform.

In addition to proudly serving his nation, perhaps the most important effect of Ephraim’s wartime experience was that he personally saw the mighty nation he loved and was defending, and made friends from all bounds of the northern United States. His wartime journey took him from the mountains of Somerset County to the battlefields of Virginia, and then to hospitals and posts in such cities as Philadelphia; Washington D.C.; Richmond; New York City; Albany, N.Y.; Columbus and Cincinnati, Ohio; and Indianapolis. The back of his diary contains signatures of friends he made, fellow invalid soldiers from Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont and West Virginia. His eyes beheld the shattered bodies of friends; the not-yet-finished capitol building in the District of Columbia; teeming hospitals with hundreds of wounded men in conditions of indescribable horror; and the railroads linking the nation’s major cities.

Everything Ephraim would do for the rest of his life would be seen through a completely different lens than before. Returning to his quiet sheltered farming village of Kingwood, he rebuilt his health and strength; married and had sons; lost his wife at a young age; remarried again; had three more children; and dealt with two sons having significant mental disabilities. Deeply Christian, he imparted a love of faith and family to his offspring, and his example endures today in the lives of hundreds of his descendants.

|

Ephraim's lifetime home, the Hexebarger valley, Kingwood, Somerset County, PA |

Early Life in Rural Somerset County

Ephraim was born in the mountains of Hexebarger near Kingwood, Somerset County, on July 1, 1838, the son of Henry and Polly (Younkin) Minerd. His parents were cousins to each other, and he is believed to have been named for an uncle, Ephraim Younkin. As an adult, Ephraim was married twice, and both his brides were local kin – Joanna Younkin (a cousin on his mother’s side, from Paddytown) and Rosetta Harbaugh (a second cousin on his father’s side, from Scullton).

Although marriages of first cousins today are illegal in Pennsylvania, they were prized then, especially in rural communities where clusters of families lived of the same ethnic background and cultures. People of the 1800s had no knowledge of modern genetic research (which became a recognized science in the early 1900s), nor were there laws to prohibit intra-family unions. In fact, cousin marriages had value to ensure that like-minded couples with similar values and heritage stayed together. It may be surprising to learn that President Thomas Jefferson urged both of his daughters to wed cousins, and in fact they did.

As a boy, Ephraim attended some school and learned basic reading and writing, though his diaries later show an inability to spell consistently or to form anything more than basic sentences. In fact, he used the family surname of “Minerd” indiscriminately with “Minard” and “Miner” and in some Civil War records the name is printed as “Minor.” In the decades before Social Security and the Internal Revenue Service forced Americans to spell their names with exact precision, Ephraim apparently did not care which spelling he used, much as someone today named “William” might not really mind if called by Will, Bill, Willie or Billy.

Ephraim grew up in a family compound of steep farms, comprising about 500 acres which his grandfather Jacob Minerd Jr. had acquired in 1837. Ephraim’s father Henry and uncles John, Jacob III and Charles each shared a quarter section of the farm, of about 125 acres each. On the Minerd side of the family , Ephraim would have known 16 first cousins living on four adjacent farms within a radius of less than one mile, and another 36 first cousins living elsewhere, all born within a 46 year span from 1827 to 1873. He also had scores of Younkin cousins in the region. During the Civil War, at least 107 of his cousins nationwide joined the military, including seven from Kingwood.

As a boy, Ephraim raced horses through the fields with his brother Chance. He also spent time with his maternal grandfather, John J. "Yankee John" Younkin. According to one story, Ephraim was shooting game for Yankee John, who was watching nearby on his horse, and when the shot was fired, the horse became excited, fell over a hill and was killed.

He also witnessed a triple tragedy involving his mother Polly, but miraculously may have helped to save her life. She was epileptic, and once, while holding a baby, had a seizure and fell headlong into a burning fireplace, burning off her ear and hair, and killing the child. In one version of the story, Ephraim somehow had the presence of mind to pull her out of the fire, saving her life. He later gave credit to God for giving him the strength. A grandmother, witnessing the horror, went running out to the fields to call for help, but fell over dead from the excitement. In another version, the grandmother pulled Polly out of the fire, but died of fright after seeing the extent of her burns.

In his early teens, Ephraim and his family survived a terrible house fire, said to have destroyed everything but the shirts on their backs. Sometime afterward, his parents sold their farm at a loss and moved to another one a short distance away. In the mid-to-late 1850s, Ephraim’s parents and younger siblings migrated to the northern panhandle of Virginia (later West Virginia). Within a year or two they relocated again, crossing back over the state line into Pennsylvania . Ephraim remained behind in Hexebarger, in the care of relatives or friends.

|

Ephraim's house of worship, the Old Bethel Church of God |

At the age of 20 or 21, in Ephraim in his "young manhood... gave his heart to Jesus Christ, and united with the Church of God at Old Bethel, in Upper Turkeyfoot," said the Somerset County Leader. Old Bethel was the first Church of God planted in Somerset County, and Ephraim is acknowledged in a history of the congregation as "an active member..." It was a symbol of a national religious renewal among German-Americans in the 1830s and '40s, and was especially strong in Kingwood.

|

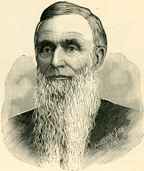

| Ephraim's spiritual leader, Rev. John Hickernell |

The Church of God movement was founded by Rev. John Winebrenner, whose roots were in the German Reformed Church. One of Winebrenner's chief colleagues, Rev. John Hickernell, helped establish Ephraim’s home church, Old Bethel, and performed Ephraim’s marriage ceremony to Rosetta Harbaugh.

When the federal census was taken in 1860, Ephraim boarded in the home of farmers John and Elisabeth Dumbauld near Kingwood. They were neighbors to Ephraim's uncle and aunt, Andrew and Susan (Younkin) Schrock, and 68-year-old widowed grandfather, Yankee John.

At age 24, some 16 months after the Civil War began, Ephraim enlisted in the 142nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Stoyestown, Somerset County on Aug. 1, 1862. Enlistment records show he stood 5 feet, 10 inches tall, had dark eyes and dark hair, and a fair complexion. He received an immediate bounty payment of $25.

Also joining the 142nd Pennsylvania were his first cousin Martin Miner, whom he considered a brother, and a cousin by marriage, Andrew Jackson Rose Sr. They traveled to state capitol of Harrisburg to be mustered into the regiment.

Ephraim’s enlistment immediately exposed him to a wide variety of men and cultural backgrounds with which he would have been unfamiliar. George R. Snowden, captain of the regiment, later said:

As much could have been expected and foretold from the character of the men who filled up its ranks, for they represented the diverse pursuits and composite character of the American citizen. Among them were the followers of the learned professions, men in business, bankers, mechanics of all kinds, drillers of oil-wells, miners of coal and iron, farmers, clerks, producers and manufacturers of lumber, teachers – in fact of almost every branch of industry – and generous and spirited boys from school, college, and the shop. The sturdy Pennsylvania Dutch were there, with their simple ways and honest hearts; the stern and resolute Scotch-Irish, the indomitable Welsh, the pertinacious English, the gallant and impetuous Irish, the steadfast Scotch, and the American of every extraction, Protestant and Catholic, all met on the same level of citizenship and patriotism.

|

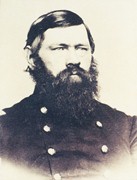

| Commanding officer R.P. Cummins of the 142nd Pennsylvania Infantry |

In September, without any basic training, the 142nd Pennsylvania was sent to Washington, D.C., “arriving there just as the wounded were coming in from the second battle of Bull Run,” reported one of the commanding officers of the regiment, Gen. Horatio Nelson Warren. “We learned from the wounded, who were flocking into the city, that the Army of the Potomac had been put to flight, and most severely handled…” It was the first time most of the members of the regiment had seen the “dome of the great capitol building.”

The 142nd Pennsylvania, led by Col. Robert P. Cummins, was placed in the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, 1st Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin and Maj. Gen. George Meade. Its first activity in Washington included guard duty and trench digging. “This was our first picket duty,” Warren said, “and, as yet, some of my men scarcely knew how to load a musket, and, while there may not have been an enemy within twenty miles, we could peer out into the darkness in our front and, in our imagination, see long lines of the enemy marching and counter-marching and getting ready to sweep us from the face of the earth.”

|

| Division commander Maj. Gen. George Meade |

They watched as other Union regiments marched out of the city, toward Maryland where they would face Confederate forces at South Mountain and Antietam. Within the week, the 142nd Pennsylvania was ordered to Frederick to provide care for the wounded of those battles. For the first time, these raw, untrained men observed “the horrible results of these battles,” Warren said, “as we saw them and heard of them from the mouths of those that were sent there, shattered and torn in every conceivable shape by bullets and shells…”

In late October, the 142nd Pennsylvania marched to Antietam and Harper’s Ferry to join the massing Army of the Potomac. Reported Warren, “This march was fraught with much that was trying to our experience,” he said, “for, as yet, our men knew nothing about foraging, little about cooking and less about taking care of and dispensing their rations… In consequence of this, half of the time we were nearly starved.”

During one halt, at Starvation Hollow, the hungry men caught their first glimpse of Gen. Meade, the commanding officer of their division. As he rode by, they shouted “crackers and hard-tack so loud and long at him, [and] in his wrath he ordered the whole division under arms and made them stand in the rain for about two hours,” Warren lamented. Their final stop, before reaching Fredericksburg, was Berk’s Station.

Be sure to reserve your copy today, so you do not miss the remaining chapters about Ephraim's saga.

Return to Overview | Return to Introduction